FAIRIES OF THE WORLD

Introduction to the Spirits of Nature

As Above, So Below

In the realms beyond our senses live innumerable other beings. Cultures around the world refer to these inhuman spirits by a variety of names and forms. People in Europe have called these entities fae (also spelled fey or fay) since the medieval era, and the word remains an inclusive term for many different spirits. Some are massive, some miniscule. Some are friendly, some mischievous, some deadly, and some worthy of more veneration.

Fairies such as Morgan le Fay from the legend of King Arthur originate from Pagan deities like the Morrígan. As their worship diminished over time, so did their size. Brân the Blessed (or Bendigeidfran) was so massive in the Mabinogion that he could wade across the Celtic Sea from Wales to Ireland; but now, the little folk often hide unseen.

Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of Invasions) tells of the Tuatha Dé Danann (People of the Goddess Danu), who once ruled prosperously over Ireland until the arrival of the Milesians (the Gaels). Ever since their defeat, the Tuatha Dé have lived in the otherworldly realm of Tír na nÓg. Also called the aos sí, they pass through portals at sacred sites like stone rings and burial mounds. Welsh myth tells of the tylwyth teg, who cross over between Earth and Annwn (or Annwfn). Evidence of their lingering presence above and below ground exists in fairy forts and fairy rings of mushrooms.

Some writers have attempted to assign political divisions to the fae with fairy kings or fairy queens, but the fae seem to have no official hierarchy. In order to see them in a more tangible way, we have to look at the world through animist eyes. Everything imaginable has a spirit. Every mountain, every forest, every town, every creek, every field, every tree, every animal, every stone has a name and a face. Before the advent of Christianity, the Romans venerated these spirits of place as the genii loci.

According to Norse cosmology, the universe exists on nine layers of the world tree Yggdrasil, with different spirits populating each level. Humans reside on the material plane Midgard (Middle Earth). In the Jewish mystical system of Kabbalah, thought to have originated thousands of years ago, the Tree of Life has ten nodes called sephiroth corresponding astrologically to each layer of reality. At the base of the tree lies Malkuth, which represents Earth and the physical world.

Even modern scientists have proposed the existence of extra dimensions—as many as 26, according to bosonic string theory. Perhaps we can only travel to Fairyland through imagination; or perhaps we already live there, unable to perceive beyond our capacity for understanding.

Varieties of Fairy Folk

Elves: Often used as a synonym for the fae, elves in Germanic mythology came into existence like maggots feeding on the rotting corpse of the giant Ymir. In Wales they are also called ellyllon. Elves have been central figures in modern fantasy literature ever since Lord Dunsany wrote The King of Elfland’s Daughter in 1924, inspiring J. R. R. Tolkien to conceptually build the world of Middle Earth for The Lord of the Rings.

Sylphs: Paracelsus, the pre-eminent alchemist of the Northern Renaissance, first described sylphs as air elementals. Possibly from the Latin word silvestris, meaning forest, they preside over the ethereal realm. One notable sylph includes Ariel, an “airy spirit” from The Tempest.

Sprites: As their name suggests, sprites are a type of spirit without form. Generally the term refers to air and water elementals.

Pixies: According to Cornish folklore, pixies (or piskies) congregate around stone rings and burial sites. They have quite a reputation for playing tricks and partying all night. In the original version of the Three Little Pigs story, the pigs were actually pixies.

Spriggans: Also from Cornwall, spriggans tend to hang out around cairns, as well as ancient barrows and ruins. Spriggans are often mistaken for trolls because of their grotesque appearance and ability to enlarge their size.

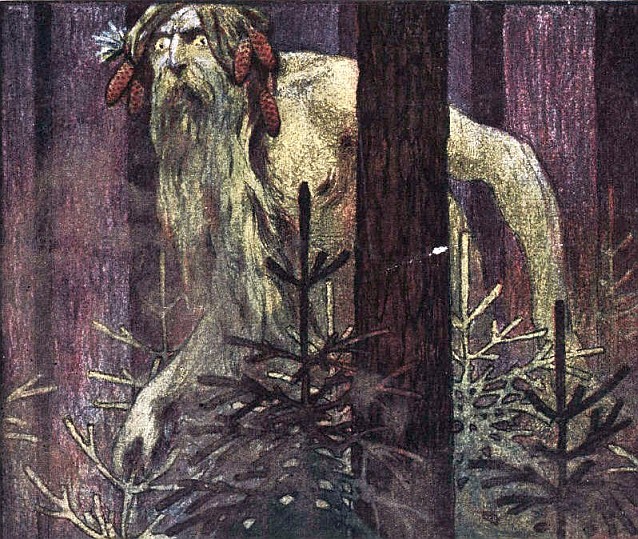

Leshies: Slavic mythology teaches about many spirits in the vast northern forests, perhaps the most significant being the leshies. Leshy is both the name of a deity as well as his companions. Within the forest, they guard the trees like gigantic ents; but if they leave, they shrink down to the size of an insect.

Dryads: Greek mythology assigns a distinct spirit to every species of tree, so the term dryad originally referred to oak nymphs. Over time it has now come to include all tree spirits.

Moss folk: Moss folk live in forests attached to the trees, where they teach people about foraging from the wild for medicine.

Gnomes: One of the creatures described by Paracelsus, gnomes are earth elementals of a rather small size. If shown respect, gnomes like to help out with chores in the garden.

Dwarves: Dwarves (or dwarfs) first appear in Germanic mythology as dark elves, living underground after their creation. Modern literature like the works of Tolkien describes them as expert miners and metal-smiths, but long ago people also thought dwarves caused them illness.

Tommyknockers: Miners have long told of spirits living underground called knockers or tommyknockers, some protective and some malicious. In Wales they are also called coblynau.

Trolls: During the day, trolls disguise themselves as rock formations in the landscape. In the northern isles of Scotland they are also called trows. As with some of the other fairy folk listed, fantasy writers like Tolkien have adopted trolls into their own worlds.

Goblins: No matter the cultural context, goblins have a mischievous reputation. Also called orcs, goblins take on the characteristics of revenant beings in the writings of Tolkien as corrupted elves. Calling them orcs suggests they could even be undead, reanimated corpses possessed by malevolent entities. Although etymologically related to coblynau, goblins behave with malice against humans.

Ghouls: Also called draugr in Germanic folklore or barrow-wights by Tolkien, these corporeal entities of Arabic folklore spread terror from the otherworld by haunting burial mounds, tombs, and cemeteries.

Red caps: So named because they dye their hats with blood from the people they kill, red caps lurk at ruined and abandoned sites waiting for more victims.

Imps: Often considered companions of the Devil by Christians, imps can be naughty little assistants. Witches and magical practitioners have been known to convince them to work on their behalf as familiar spirits.

Genies: Known in the Arabic world as the jinn or djinn, genies take on different forms. Belief in the jinn goes back to ancient times, when the Babylonians worshipped a wind deity named Pazuzu—now sometimes referred to as a demon.

Hags: Various religious traditions have divine hags in their pantheons, often as a crone aspect of the Triple Goddess archetype. Gaelic myths tell of Beira, also known the Cailleach, while gwyllion haunt the mountain peaks of Wales.

Hobs: Hobs or Hobgoblins often take up residence inside of human dwellings, making a home in some forgotten corner of the building. While the primary occupants are not watching, they might perform household chores or mischievous tricks.

Brownies: While in English houses they have hobgoblins, in Scottish houses they have brownies. In Wales these domestic spirits are also called bwbachod, and in Germany they are called kobolds.

Nisse: In Scandinavian folklore, nisse (or tomte) live alongside humans around the time of the winter solstice. With their conical hats, they resemble a type of gnome which guards the family and their land. In Finland they are also called tonttu.

Iratxoak: Basque mythology has a helpful fairy known as an iratxoak, which likes tending to chores on the farm in their red pants.

Tinkers: Like the fairy Tinker Bell described by J. M. Barrie in Peter Pan, tinkers make or mend metal objects.

Leprechauns: As everyone already knows, leprechauns guard their pots of gold at the end of rainbows. They spend most of their time alone, making shoes and pulling harmless pranks on humans. Centuries ago they wore red clothes, but more recently they seem to prefer green.

Clurichauns: Considered one of the solitary fae, clurichauns have a fondness for alcohol and loiter around breweries, pubs, and wine cellars.

Pucks: Also known as the pooka (or púca), puck has the ability to shapeshift into different animals like goats, horses, cats, dogs, and hares—usually with black fur. Somewhat like the character from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the pooka likes to trick people as well as help them. After the final harvest of Samhain, farmers once gave whatever remains in the fields to fairies such as the pooka as an offering of peace.

Changelings: Fairy folk have a notorious reputation for kidnapping human children and leaving behind their own offspring instead, known as changelings. While many of the spirits listed here have faced such accusations, perhaps the most guilty might be the rat boys (known as the far darrig in Ireland).

Banshee: Known for their spectral keening, banshees warn of impending death in the family. They often appear in the form of a woman in white like a Gaelic goddess named the Morrígan.

Mares: These malicious entities sit on top of people while asleep and bring them terrible dreams like a soul-sucking cat from Hell—hence the term nightmare.

Boggarts and boggles: Boggarts, boggles, and bogeys have a clear disdain for big folk. Mostly found in wetlands like bogs, swamps, and marshes, they also come into homes and terrorize those living there. When feeling especially vengeful, they can even follow people who move to a different house trying to escape. Over time these creatures have become boogie monsters hiding in the closet or under the bed.

Will-o’-the-wisps: Known by various names around the world (ignes fatuus, ghost lights, spook lights, jack-o-lanterns), will-o’-the-wisps appear in forests and wetlands as a spectral glowing orb without any obvious source of illumination. Scientists have attempted to explain this worldwide phenomenon as a type of bioluminescence or chemiluminescence—no worries, just flaming bubbles of swamp gas. Commonly mistaken for spirits of the dead, will-o’-the-wisps have a grim reputation for leading people to their demise or leaving them lost in the woods.

Merfolk: Merfolk include merpeople, mermaids, mermen, and other hominids of the sea and coastal regions. As everyone already knows, merfolk have a hybrid anatomy of human and fish. Yet, different cultures depict this in various ways.

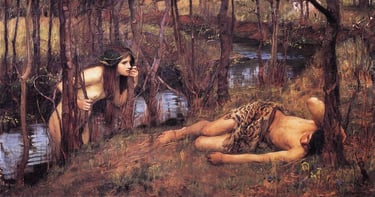

Naiads: Greek mythology describes how naiads inhabit freshwater streams, lakes, springs, and wells in the form of a nymph or youthful female nature spirit.

Nixies: Also called nix, nixies can shapeshift into whatever form they please. Sometimes they prefer the form of a wyrm or dragon, swimming in lakes and rivers. With their siren songs, they lure people to death by drowning. Slavic cultures refer to these malevolent fairies as rusalki.

Undines: One of the four elementals described by Paracelsus, undines are a general term for water spirits.

Salamanders: Not the same as the amphibian they share a name with, these salamanders live in fire. Spirits made of flame might conjure a frightening image, but salamanders can provide warmth and light when people need them most.

Native American Little People: Fairies and elves are called yunwi tsunsdi’ by the Cherokee, while the Wampanoag tell of shapeshifters called pukwudgies, which often appear like a quilled porcupine with humanoid features. According to the Catawba, the yehasuri live within tree stumps, feeding on frogs and insects. Other names for the Native American Little People include the jogah from the Iroquois, mannegishi from the Cree, and mikumwess from the Wabanaki.

Angels and Demons

Within the binary framework of Christianity, angels and demons represent the powers of lightness and darkness struggling for control over the cosmos. Fairies share many qualities of both, as winged spirits of nature existing in unseen realms. Ever since the Roman Empire adopted Christianity in the fourth century, the concept of angels and demons has played a central role in the erasure of Pagan perspectives. Norse mythological sources, like the Prose Edda written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, divided their classification of nature spirits into light elves and dark elves based on Christian ideas of good and evil. Through a process of demonization, the many creatures found in animistic religions became in conflict with an imperial monotheistic system. In some cases the Christian Church adopted local deities as saints, such as the Celtic goddess Brigid, to syncretize the Indigenous perspective with the invading Christian dogma.

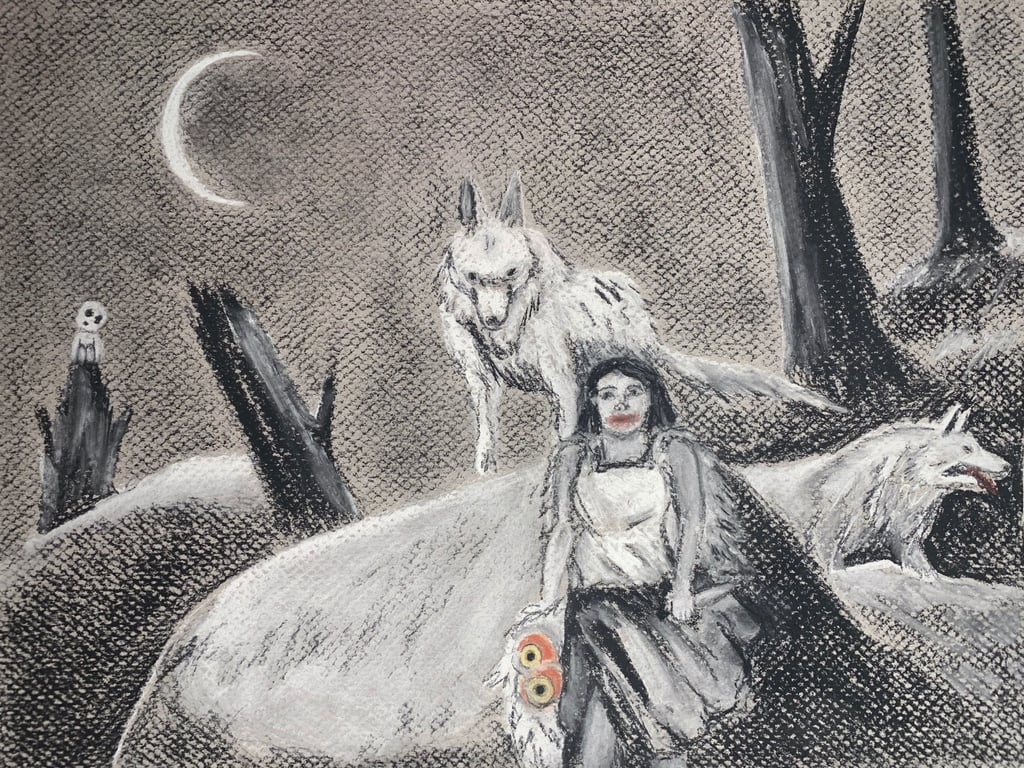

As a result of this war against nature, some fairies fled into the shadows festering with anger and resent. Studio Ghibli presents a similar perspective in the 1997 animated film Princess Mononoke. When the people of Iron Town decide to kill the Forest Spirit, other deities of nature attempt to fight back and in the process become just as monstrous as the humans.

Resurrection of the Meadow

Humans have much to learn from the fae and all the spirits of the wild. By keeping their stories alive through fairy tales and folklore, we can live in closer connection to our environment. Although not visible to the eyes, the wee folk manifest through art and imagination. Building our society around existing features instead of clear-cutting and paving over paradise shows respect and veneration for the planet, welcoming the spirits back into the land. Planting more gardens and more trees will provide habitats for them to move in, along with setting aside special corners of the home inside. Simple offerings like water, honey, or pastries might give some protection from their unpredictable temperament.

As the global climate changes more and more every day, who knows what else might awaken?

FAERIES OF THE WORLD

Introduction to the Spirits of Nature

SUBSCRIBE

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates about the Temple of the Fae directly to your inbox.